Despite having a thriving furniture design and manufacturing industry throughout the middle of the twentieth century, the UK has largely been overlooked during the revival of interest in modern furniture design. An early, misplaced, perception, that the work from Great Britain was less interesting than from Scandinavian nations, Brazil, or the United States of America, meant that dealers and auction houses offered little in the way of British design, leading to collectors ignorant of its existence. In fact British modernist design began pre-WW2, and thrived post-war through a creative approach to design and application of materials, as the UK went from rationing to the post-war boom in the late 1950s and 1960s.

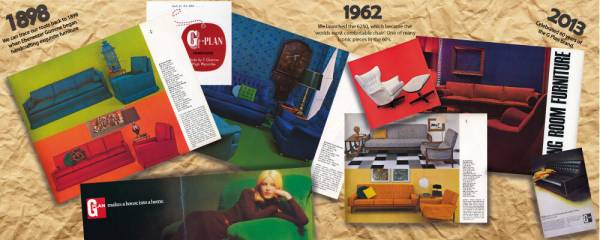

Like Denmark, Britain’s modernist movement started in the 1930s, with makers and designers such as Gerald Summers, who, with his wife Marjorie Amy Butcher, founded the Makers of Simple Furniture in 1931. Summers exploited the use and singular properties of aeroplane plywood to make furniture with curved surfaces and curvilinear outlines, such as his bent wood plywood armchair. Unfortunately Makers of Simple Furniture were only a small company and weren’t able to survive the second world war, due to the reservation of plywood for only military use. Other companies, however, benefited from the industry surrounding the war: for example, the wartime mechanism pushed the E. Gomme factory to become more efficient, paving the way for their post-war expansion and the subsequent launch of G-Plan in 1952. Post-war Britain was left in ruins, with rationing remaining in place until 1954, and the Utility Furniture Scheme only ending in December 1952.

Post-war, designers faced the daunting task of creating furniture, within rationing measures, that could help rebuild the nation. As Geoffrey Rayner has noted: “Furniture design would take a leading role in projecting a vital, modern, go-ahead image for Britain….Well designed modern furniture was also seen as an essential ingredient for successfully obtaining export orders, so necessary for Britain’s economic recovery.” A nice example of innovation from this time include Ernest Race’s side chair, produced in 1946, its frame made of resulted aluminium obtained from aircraft scrap.

While 1946’s Britain Can Make It exhibition whetted the public appetite for modern design, it was the Festival of Britain, in 1951, that really brought British modern design to the attention of the UK and internationally. Along with some classic modern architecture like the Royal Festival Hall (designed by Leslie Martin), modern furniture design was both on show and utilised; Ernest Race’s Antelope Chair (which is still in production today), was chosen for use on the festival’s cafe terrace, and Robin Day was commissioned to design the seating for Royal Festival Hall, creating a design classic in his rosewood veneered, bent plywood, lounge chairs, designed for the hall’s lounge and restaurant.

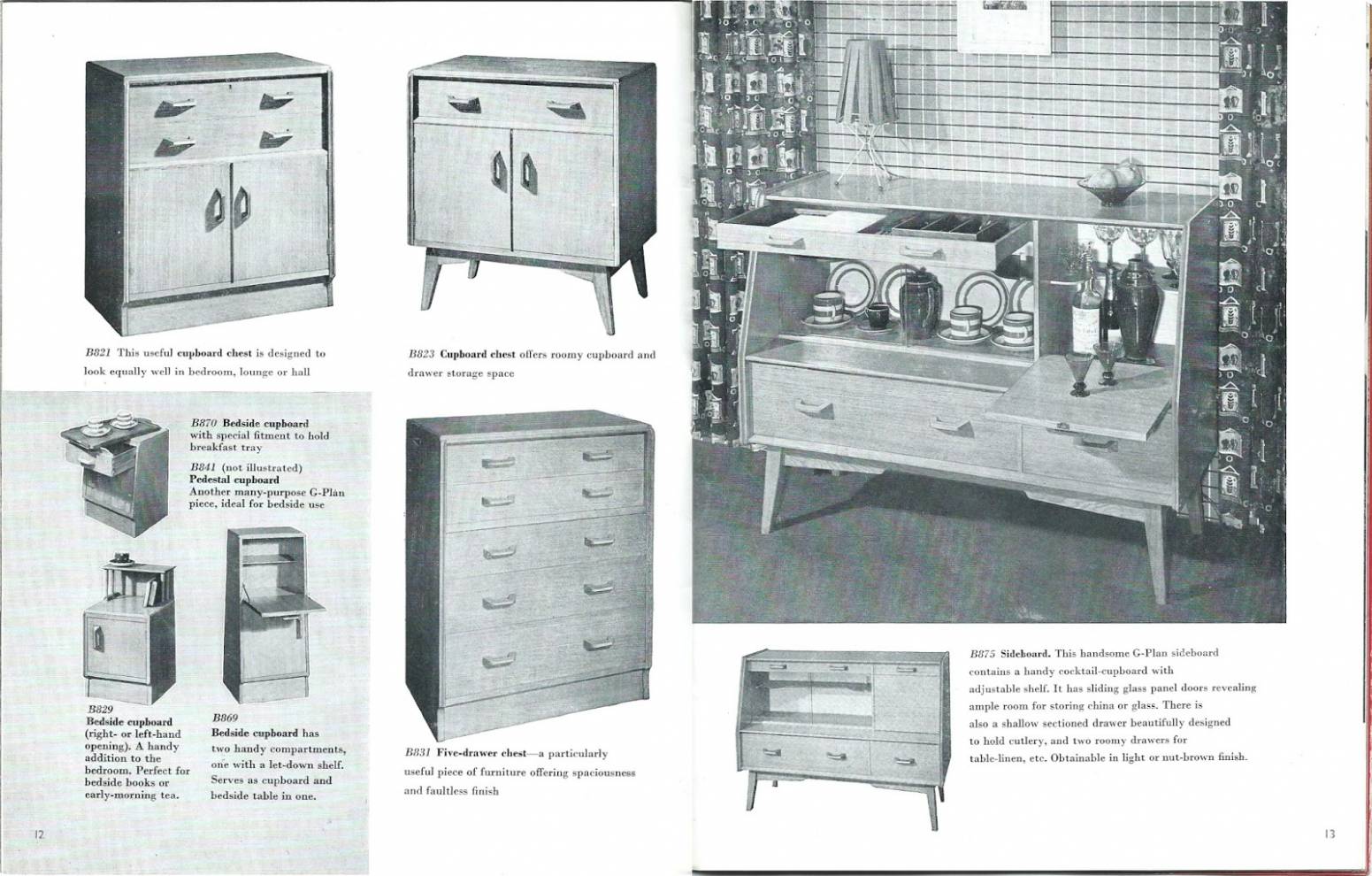

Throughout the late 1950s and 1960s the British furniture design and manufacturing industry were influenced by the Danish modern school, both with importing furniture from Scandinavian producers, and British designers and manufactures taking inspiration from the Danish principles of human centred, well made furniture. Companies such as G Plan, and McIntosh took inspiration from the Danish modern school and made it their own; Danish designer Ib Koford-Larsen worked with G Plan through this era, designing pieces for the Librenza and Fresco range as well as leading the G Plan Danish range, launched in 1962.

Prominent designers and manufacturers of British modern furniture through this period include: G Plan, McIntosh, Ercol, Hille, Lucian Ercolani (Italian founder of Ercol), Ib Kofod-Larsen (G Plan), Victor Bramwell Wilkins (G Plan), Ernest Race, Robin Day, Robert Heritage, and John and Sylvia Reid.

By the end of the 1950s, and into the early 1960s, British modern furniture had become more utilitarian and sober in character. Designers like architects John and Sylvia Reid brought their functionalist approach to bear on furniture design. Their work was rectilinear in form, and executed in dark woods, with little ornamentation; it was machine made, and meant to look like it.

‘As stark as it was, the Reids’ furniture is a success. It was a reminder to the public that in a little over ten years they had gone from a life of blitzkrieg, buzz bombs, and rationing coupons to one of stylish and dignified modernity.’ Gregory Cerio - ‘The Magazine Antiques’

All Restoration